BORN NOVEMBER 6, 1915

PALISADES, NEW JERSEY, USA

If Alfred and the first American Parkyns thought they’d

escaped the harsher side of life when they put London’s Mile End behind them,

they were wrong. Alfred saw the impact on the family of his uncle’s Edward’s death

in France at the end of the First World War. Memories of Edward must surely

have faded in young Alfred’s memory by the time Edward became the namesake of

his town’s American Legion post. Tragedy didn’t end with the end of war. Alfred

lost his 11-year-old brother during Alfred’s senior year in high school. Two

years later, Alfred’s 50-year-old father passed away. The successive losses

left Alfred’s mourning mother and sisters reeling but undoubtedly grateful for

his stabilizing presence in the family. By 1940, Alfred’s life was on a course

that kept him close to home. At 26 years of age, Alfred had a steady but menial

job in the Bronx. His elder sister had married, leaving Alfred at home with his

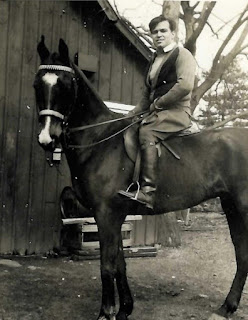

mother and 13-year-old sister Renee, who adored the big brother she knew as

Allie. Over the course of 30 years, the Parkyn family’s exuberance and success

had, through family tragedy and economic disaster, given way to a grittier

determination to persevere together.

Alfred harbored dreams of becoming a pilot, but he was both

too old and lacked the bachelor’s degree required for military pilot programs.

Opportunities in civil aviation were scarce, and flight training wasn’t cheap.

With his spare income, Alfred had managed to accumulate a meager eight hours of

flight time and was making payments on a ground school course he’d taken.

At some time during the summer of 1940, Alfred must have

come across one of the recruiting advertisements posted at municipal airports

by the Clayton Knight Committee. Replete with images of Spitfire fighter

planes, the flyers sought men for the Royal Canadian Air Force, and steered

applicants to Knight’s shadow organization at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. The

Waldorf was on Alfred’s route home from work, but Alfred’s workday clothes would

not have been in keeping with the hotel’s splendor; he must have made a trip

from home, in his best clothes, when he applied.

And he did apply. His move must have concerned family

elders, who would have numbered themselves among America’s isolationist population

after Uncle Edward’s death. Without a steady income or husband, his mother must

have found Alfred’s decision to be alarming.

Winning his wings in November 1940, Alfred flew home for a

brief visit. Once in England, he wasted no time in connecting with family in

Surrey, which became his favorite destination during leave periods. He wrote

dutifully to his mother and sister, sending photos of “his” room above a Surrey

shop, and the Earl Beatty Pub, where he enjoyed a pint now and then.

Alfred must have seemed brash and outspoken to his British

squadron mates, as many Americans did. He was fond of them, describing them in

a 1942 interview as “hard to get next to, sometimes,” but noted “they have

horse sense. These guys know their racket.” Little memory exists of Alfred’s

relationships with his fellow aviators – of the 400-plus men he could have met

while flying with 207 Squadron, half were dead within a year of his final

mission. Bomber Command’s low attrition – 3 percent

– equated to certain death for aircrew within 34 missions.

Mere months after arriving at his bomber squadron, Alfred

failed to return from a mission. His death was the fourth tragedy to strike the

Parkyn’s in 20 years. After the war’s end, those

surviving family members worried about work and the future. They moved apart to

the corners of the United States leaving Alfred’s fading story behind them.

Alfred’s sisters never got over their sense of loss. Years

later, the family children would remember his sisters, Gladys and Renee, speaking of

their beloved brother "Allie" still haunted by the vague nature of his fate –

missing, presumed dead, with no known grave.